Overweight and obesity classification: BMI & other methods

Last Updated : 18 October 2024Recent estimates suggest that about 880 million adults and 159 million children are living with overweight and obesity.1 But what does overweight and obesity mean? And how are they classified, and why should we care? Understanding these classifications is important for our health because they help us assess our risk for various diseases, manage our weight effectively, and guide us in making healthier lifestyle choices. This article explores the most common method of classification, the Body Mass Index (BMI), its formula, and limitations, as well as other methods that measure body fatness. The BMI scale is used together with other factors to diagnose obesity.

Obesity classification

Overweight and obesity both describe conditions of excessive body fat that presents a risk to health.2 Excessive fat deposits increase our risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease, certain cancers, and can affect bone health and reproduction, amongst other health risks . Overweight and obesity classifications help healthcare providers assess the likelihood of weight-related health issues.

Overweight and obesity can be measured in different ways, but the most common measure is the body mass index (BMI) in adults. The BMI determines the relationship between weight and height by dividing one's weight in kilograms by the square of their height in metres (kg/m2). Although the BMI does not offer a direct measure of body fatness, it is recognised as a practical approach in clinical or health monitoring settings as height and weight measurements are non-invasive and do not require specialised skills or expensive equipment.2

Based on the BMI calculation it categorises individuals into different classes: with underweight, normal weight, overweight or obese (Table 1).2 These cut-offs are the same across different ages and sex for adults and have been found to be associated with health outcomes, including mortality.

The European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO) recommends that BMI, together with a waist-to-height ratio equal or larger than 0.5 and medical, functional or psychological impairment or complications, are used to diagnose obesity. This means looking at not just the physical aspects of obesity, but also, for example, mental health (e.g., evaluating for depression, anxiety, and eating disorders) and eating behaviours (e.g., emotional eating, binge eating, restrictive eating). This is because BMI cut-off values do not reflect the role of body fat distribution and the severity of the condition. This new framework provides a more complete clinical evaluation of individuals with obesity.3

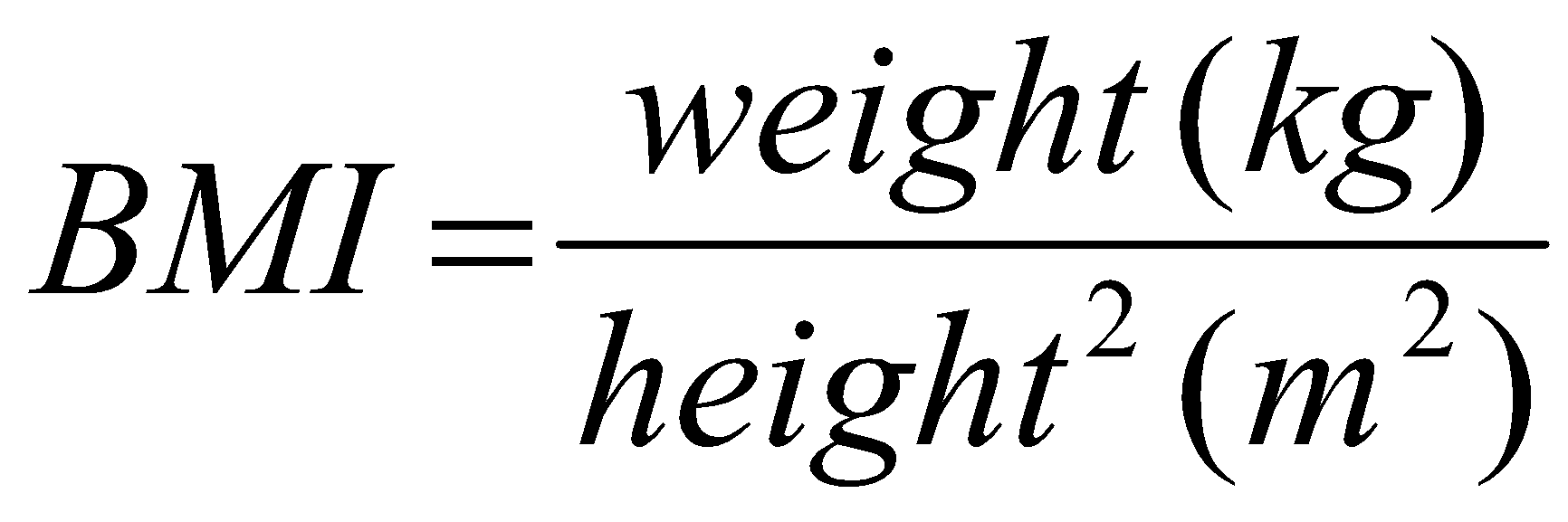

BMI formula

The BMI is defined as the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres (kg/m2).2 For example, an adult who weighs 70 kg and whose height is 1.75 m will have a BMI of 22.9 kg/m2. This would place you in the ‘normal weight’ category according to standard BMI

classifications.

Body Mass Index (BMI) formula:

For children and adolescents, BMI is interpreted differently.4,5 Since children and adolescents are still growing, BMI percentiles are used to compare their BMI with others of the same age and sex. Growth charts and percentiles are used to monitor these changes over time.

During pregnancy, the BMI is also evaluated differently. The focus is on appropriate weight gain throughout the pregnancy rather than a specific BMI range. Health professionals monitor weight gain to ensure it is within a healthy range for both the mother and the developing baby, considering pre-pregnancy BMI and individual health conditions.

For people of Asian, Chinese, Middle Eastern, Black African or African-Caribbean background, the BMI is also interpreted differently.2 This is because the same BMI may not correspond to the same amount of fat mass across different ethnic groups. For example, among South Asian individuals, a higher percentage of body fat and a greater risk of ill health have been found at a lower BMI.

Table 1 – Overweight and obesity classification for children under five years, children between 5-19 years, adults, and people of Asian, Chinese, Middle Eastern, Black African or African-Caribbean background.2,4,5

|

Children under 5 years |

Children between 5-19 years |

Adults |

Asian, Chinese, Middle Eastern, Black African or African-Caribbean background |

|

|

With overweight |

Weight-for-height greater than 2 standard deviations above WHO Child Growth Standards median |

BMI-for-age greater than 1 standard deviation above the WHO Growth Reference median |

BMI between 24.9 – 29.9 |

BMI between 23 – 27.4 |

|

With obesity |

Weight-for-height greater than 3 standard deviations above the WHO Child Growth Standards median |

BMI-for-age greater than 2 standard deviations above the WHO Growth Reference median |

BMI ≥30 |

BMI ≥27.5 |

The limitations of BMI

While the BMI is a popular tool for categorising weight, it comes with several limitations that can lead to misleading conclusions about an individual's health status. The BMI treats all body mass – including fat, muscle, organs, and bone structure – as equally risky for health.6However, this is not the case. The BMI does not give us information about the total fat or how the fat is distributed in our body, which is important as excess abdominal fat can have health consequences. We know that visceral fat, the fat stored in the abdomen around the internal organs, is more strongly associated with poor health outcomes.2 In contrast, subcutaneous fat, which is the fat stored just under the skin and is distributed across the body, has less of a risk. For example, if fat is stored mostly on someone’s hips and thighs, they have a lower risk of disease than if they store the fat around their abdomen. A muscular athlete might also have a high BMI but low body fat and be in excellent health, whereas someone with a high percentage of body fat and low muscle mass might have the same BMI but be at a higher risk for health issues.

Additionally, (adult) BMI does not account for factors such as age, gender, and ethnicity.6 It is not as accurate a predictor of body fat in the elderly as it is in younger and middle-aged adults. Asians also have a higher body fat than people from a white family background, and women have, on average, more body fat than men, requiring more careful interpretation.

Nevertheless, the BMI is, in general, a helpful indicator of a healthy weight for most people and the index has been found to be a reasonable proxy when used for large numbers of people. Correlations have been found between the BMI and total body fat and total abdominal fat tissue.2 It is rare to see someone with a BMI of 30 and above and who does not have excess fat tissue presenting a health risk.7 The BMI is also correlated with bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) and the more complex and costly dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) technique, which is a more precise method to measure the amount of lean and fat tissues.8 This method and other methods that are used to more accurately measure the amount of visceral fat, such as computed tomography (CT), would not be scalable to the population level.

In summary, the BMI should be more carefully interpreted on an individual basis for:

- Pregnant women.

- Athletes or people with a high muscle mass. This is because they can be classified living with overweight or obesity on the BMI scale, even if they have a low or healthy body fat percentage.

- Elderly individuals. This is because muscle and bone density tend to decline with age. As a result, they may have a higher body fat percentage compared to younger individuals with the same BMI. Having a slightly higher BMI when older may also have a possible protective effect on health.9

- Women. This is because they generally have a higher body fat percentage than men for a given BMI.

- Particular ethnicities – in particular, those of Asian origin. This is because they tend to store more visceral fat compared to subcutaneous fat and are therefore at a higher risk of negative health outcomes at a lower BMI.

Other methods to classify obesity

Several other methods exist to understand body composition and health risks associated with overweight and obesity. A few common alternatives include:

Waist circumference

This method measures the circumference around the narrowest part of the waist. A higher waist circumference indicates a greater amount of visceral fat and total body fat.6 If waist circumference is greater than 102 cm for men and 88 cm for women (or 90 cm and 85 cm, respectively, for Asians) it means they have excess abdominal fat, which puts them at greater risk of health problems, even if their BMI is in a normal range. The World Health Organization suggests combining BMI and waist circumference to better predict future health risks.2

Waist circumference is easy to measure, inexpensive, and also predicts development of disease and death. However, the procedure for measuring waist circumference is not standardised and there is a lack of reliable reference data for children. It is also challenging to measure and less precise for individuals with a BMI of 35 or higher.6

Waist-to-hip ratio

The waist-to-hip ratio is calculated by measuring the narrowest part of the waist and the widest diameter of the hip, and then dividing the waist measurement by the hip measurement. A higher ratio indicates a higher risk of obesity-related disease, as it suggests more fat is stored around the abdomen.6 The waist-to-hip ratio also shows a similar association with future morbidity and mortality as the BMI.2 For women, risk is classified as low when the waist-to-hip ratio is below 0.8, moderate between 0.8-0.89, and high when it is equal or higher than 0.9. For men, the risk is classified as low when the waist-to-hip ratio is below 0.9, moderate between 0.9-0.99, and high when it is equal to or higher than 1.0.9

The waist-to-hip ratio is more prone to measurement errors because it involves taking two separate measurements, and measuring the hips accurately is generally more challenging than measuring the waist. Additionally, interpreting this ratio is more complicated because a higher ratio might result from either an increase in fat around the stomach or a decrease in muscle mass around the hips. When you convert these measurements into a ratio, some information is lost. For example, two individuals with vastly different BMIs might end up with the same waist-to-hip ratio.6

Waist-to-height ratio

The waist-to-height ratio is calculated by dividing the waist circumference by one's height. It is recommended that individuals should try and keep their waist to half their height (so a waist-to-height ratio of under 0.5).9 The waist-to-height ratio can be used for men and women of all ethnicities with a BMI under 35 km/m2. Studies show that the waist-to-height ratio is closely associated with cardiovascular risk and has a clearer relationship with mortality than the BMI.10,11 The waist-to-height ratio is also better able to predict cardiometabolic risk than waist circumference.12

Body fat percentage

Body fat percentage is a measure of the total fat mass compared to overall body weight. Unlike BMI, this method differentiates between fat and lean muscle mass. Various methods can measure body fat percentage, including skinfold callipers , bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), and more advanced techniques like DEXA, CT and MRI scans , underwater weighing, and air-displacement plethysmography . Each of these methods have their own pros and cons.6

Skinfold thickness measurements are safe, inexpensive, portable, and fast to perform, however, not as accurate or reproducible as other methods and difficult to measure in individuals with a BMI of 35 or higher.6

Some health authorities advise against using bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) instead of BMI to assess overall body fat levels in adults.9 Limitations of this method include that it is difficult to calibrate, the ratio of body water to fat may change during illness, dehydration or weight loss, and it is not as accurate as other methods, especially in individuals with a BMI of 35 or higher.6

The more advanced techniques, while accurate, are expensive to conduct and equipment often cannot be moved. Underwater weighing is also time-consuming and not a good option for children, older adults, and individuals with a BMI of 40 or higher. Also, a limitation of the DEXA scan is that it cannot accurately distinguish between visceral and subcutaneous fat and cannot be used with pregnant women. CT scans also cannot be used with pregnant women or children.6

Summary

When it comes to figuring out if someone is underweight, at a healthy weight, with overweight, or with obesity, we mostly use the Body Mass Index (BMI) scale. This tool looks at your weight in relation to your height, with specific interpretations for children, adults, and various ethnic backgrounds. However, the BMI has limitations as it does not differentiate between muscle and fat and disregards differences in fat distribution and composition. For instance, visceral fat around the abdomen poses higher health risks than subcutaneous fat that sits just underneath the skin. Nevertheless, it is still widely used in population health assessments because of its simplicity to measure and strong associations with morbidity and mortality. Other, more accurate, methods such as DEXA, BIA, CT and MRI scans, underwater weighing, and air-displacement plethysmography are expensive to conduct and difficult to implement at the population level.

The article was developed in collaboration with the BETTER4U project. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 101080117.

Visit www.better4u.eu for more info.

References

- Phelps NH, et al. (2024). Worldwide trends in underweight and obesity from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 3663 population-representative studies with 222 million children, adolescents, and adults. The Lancet, 403(10431), 1027-1050.

- World Health Organization. (2022). WHO European regional obesity report 2022. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe.

- Busetto L, et al. (2024). A new framework for the diagnosis, staging and management of obesity in adults. Nature Medicine, 1-5.

- World Health Organization. (2024). Child growth standards. Accessed 30 July 2024.

- World Health Organization. (2024). Growth reference data for 5-19 years. Accessed 30 July 2024.

- Hu FB. (2008). Measurements of adiposity and body composition. Obesity epidemiology, 416, 53-83.

- Gómez-Ambrosi J, et al. (2012). Body mass index classification misses subjects with increased cardiometabolic risk factors related to elevated adiposity. International journal of obesity, 36(2), 286-294.

- Martin-Calvo N, Moreno-Galarraga L & Martinez-Gonzalez MA. Association between body mass index, waist-to-height ratio and adiposity in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients 2016; 8: 512

- "Obesity: identification and classification of overweight and obesity (update) Recommendations 1.2.25 and 1.2.26". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2022.

- Schneider HJ, et al. (2010). The predictive value of different measures of obesity for incident cardiovascular events and mortality. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 95(4), 1777-1785.

- Ashwell M, et al. (2014). Waist-to-height ratio is more predictive of years of life lost than body mass index. PloS one, 9(9), e103483.

- Ashwell M, Gunn P, & Gibson S. (2012). Waist‐to‐height ratio is a better screening tool than waist circumference and BMI for adult cardiometabolic risk factors: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity reviews, 13(3), 275-286.